Imagine you are sick, but you don’t know exactly what’s wrong. You go to the doctor and she is puzzled, too. You undergo a bunch of tests including bloodwork and a scan, and the doctor asks questions about your symptoms. Using this structured, objective process, the doctor forms a complete picture of your health and gets to the root cause of what’s ailing you. In business today, teams need the same sort of doctoring.

Teams are the primary unit of many workplaces, and their problems are diagnosed through team assessments. In this guide, we go over everything you need to know about picking the right assessment tool, how assessments work, and what assessment to use in situations such as remote teams, startup teams, and teams that struggle with trust and ineffective communication.

You’ll also find team assessment advice from 13 leading practitioners, a simple online survey to use with your team, a matrix to help you choose the right tool, and free templates.

“Teamwork” is a term that is used so frequently in professional and academic settings that it means different things to different people. Younger employees, have probably heard it so often that they’ll conflate it with group work — basically, any time they’re working with other people.

Teamwork and group work are two quite different things, even though many people don’t distinguish between them.

A group is simply a loose organization of people who coordinate their efforts. A team, by contrast, is a collection of people with shared goals who are bound by their commitment to reach these goals. They share a common purpose, and they regulate their behavior and performance to fulfill this purpose.

Since teammates share goals, they also hold each other accountable while pursuing these goals, and they have to be good communicators. Most importantly, teams are characterized by synergy, the combination of individual efforts to create a team effort that is greater than the sum of the individual efforts. Simply put, teams do things that groups can’t. That’s vital for organizations, which typically have goals stretching far beyond individual capabilities. Organizational success is built on effective teamwork.

Teams need to be built; they are not automatically fully formed and functional. That’s not to say teams can’t be created organically, but the best teams usually have members picked to fill specific roles or functions (to create synergy). Ensure that teammates complement each other and build relationships that allow them to do this most effectively.

Teammates can complement each other in terms of skills, diversity of perspectives, personalities, thinking styles, experiences, training, and social abilities. In an increasingly globalized world, even different cultural backgrounds might be an asset. Bringing diverse talents together can translate into tangible benefits.

Your one-stop shop for everything project management

Ready to get more out of your project management efforts? Visit our comprehensive project management guide for tips, best practices, and free resources to manage your work more effectively.

High-performing teams are more efficient because they coordinate their efforts better. The combination of different perspectives, thinking styles, and experiences translates into better decision making. Since these teams are better at managing themselves, they usually do a better job of sticking with their decisions, too. They are aware of what each teammate has to offer, and they usually experience less interpersonal conflict.

The strongest teams are characterized by clear, fair communication. They also have more clarity about the team’s purpose and goals, and thus more accountability. Working together is generally a positive experience, which means team members are happier — both with the team and the organization as a whole.

If teamwork is not cultivated, problems often arise. Many people who say they work on teams — which, in the modern workspace covers most of us — are actually members of pseudo-teams.

Pseudo-teams refers to groups of people who are intended to achieve team results but who do not share the common purpose and interdependence of true teams. When that happens, the results are usually suboptimal, and the teammates don’t enjoy themselves.

This might help explain why so many people say they don’t like teamwork. According to a 2013 survey by the University of Phoenix, only about one in four American workers who has ever worked on a team says they prefer it to working solo—even though almost all of them agree that teams are an important feature of the workplace. Why?

According to the survey, seven in 10 workers who have been on teams report they have been part of a dysfunctional unit at least once. Four in 10 say they have seen verbal confrontations between teammates, and about one in seven say they have seen these lead to physical confrontations. Office gossip is also a persistent problem; about one in three say they have seen teammates start rumors about each other.

When done properly, team cultivation allows people to develop an understanding for and an appreciation of what each individual brings to the table. This doesn’t preclude conflict, but it goes a long way towards minimizing it.

When rapport doesn’t exist among team members, poor personal relationships and mistrust become far more prevalent. A culture of poor or disrespectful communication is much more likely to give rise to harmful politics, and decision making suffers. When the team doesn’t have a shared purpose, they struggle to achieve, meet objectives, and deliver on time. Any of these problems result in lost synergy.

So how do you tell if your team is working the way it's supposed to? You may instinctively feel that some element of teamwork is missing or sense that you could get even better team performance if you spent time on team-working activities. But rather than guessing, you need to perform a structured team assessment to analyze, identify, and get to the bottom of issues.

A team assessment is an exercise that allows you to evaluate a team’s strengths and weaknesses. As a recognized management technique, team assessments began attracting attention in the 1970s and 1980s, after American organizational practice wholeheartedly embraced the idea of teamwork as a primary driver of success (in professional sports, which has always emphasized teamwork, different team assessments have been used for even longer).

Scholarly interest in measuring team performance followed shortly after, as Michael T. Brannick, Eduardo Salas, and Carolyn W. Prince note in their 1997 book “Team Performance Assessment and Measurement.” This trend coincided with a wider turn toward the use of formal theories and frameworks in measuring team performance. In the 1990s, team assessment methodologies adopted from professional contexts such as the military and theater were widely disseminated.

Although even an informal assessment can be helpful, team assessment tools have grown more sophisticated, applying principles from organizational theory and human resource management. Today, specialized team assessments are designed to measure multiple facets of team performance based on formal models of how teams should operate.

Team assessments can be conducted in a lot of different ways: in-person sessions, via email, or with tailor-made online surveys and apps. Many assessments use specially designed worksheets.

Some team assessments are based on particular theories about what drives effective teamwork. These include the work of management theorist Meredith Belbin, who suggested that good teamwork was predicated on the presence of different personalities on a team and having individuals who fit specific behavior roles, and of business consultant Patrick M. Lencioni who identified five major team dysfunctions.

Other assessments focus on different measures of team effectiveness, such as the quality of organizational support, clarity of goals, a team’s ability to learn and grow, team diversity (not only in terms of culture, race, gender, but also thinking styles and personalities), and, most importantly, the ability to deliver results.

Managers most commonly perform a team assessment to uncover problems and shortcomings within teams. Weaknesses may be difficult to pinpoint if you are closely involved with the team and have difficulty making an objective assessment.

A skilled outsider offers neutrality and a fresh eye. He or she generally has higher credibility with the team since the consultant is removed from organizational politics. Team members are also likely to be more willing to speak candidly with a consultant because they have more trust their confidentiality and worry less about repercussions.

While diagnosing problems is good, you should also conduct team assessments to identify fault lines where future problems might emerge. Going through the assessment process usually also strengthens a shared sense of purpose, trust, and communication among teammates. The end goal remains the same: ensuring the team is operating optimally and positively impacting the team experience.

As you prepare for a team assessment, make sure to choose a tool that matches your needs and objectives. Some assessments focus on how individuals contribute to teams: what strengths and weaknesses they bring to the table, how their behavior affects the team, and how effective their individual efforts are. Others focus on the team as a whole, evaluating the team’s processes and the quality of their results.

While team-focused assessments may be better markers of team results, which is usually the first concern for people managing teams, there’s a strong case to be made for understanding individuals before you can understand the team. And it may be worth considering a specialized assessment for your team leader, who fulfills the separate, challenging functions of coordinating, motivating, and directing the team.

To understand how team assessments can be used to improve teamwork, let’s dig a little deeper into teams — how they are set up, how they evolve, and what problems they are likely to run into.

When picking people for a team, a manager or supervisor must take into account each individual’s personality, social style, skills, and thought process. Imagine, for instance, having a team staffed solely with introverts or extroverts, or solely with creative or practical people. It probably wouldn’t work very well.

Earlier, we mentioned Belbin, a British management theorist who in 1981 described eight personality types that needed to be present (and balanced) among members of a team for the team to function optimally. Belbin’s work is among the best-known theories of how diversity impacts teams. He believed that these personality types emerged naturally, meaning the roles cannot be learned or sufficiently cultivated. So, they are a critical consideration when picking people to form a team.

Here are Belbin’s roles (including the ninth he added in 1991):

Belbin’s theory focused on naturally emerging personalities, but alternative theories focus on other characteristics. These include late business journalist Robert Heller’s seven functional roles, which relates team members to the responsibilities they take on (rather than their innate strengths), and psychologist Edward de Bono's six thinking hats, which represent different thinking styles that we all can wear at different times. Kenneth Benne's and Paul Sheats’ 26 group roles combine aspects of function and personality.

Interestingly, Benne and Sheats also described eight so-called dysfunctional roles, which could potentially harm team efforts. These included aggressors, blockers, recognition seekers, self-confessors, disruptors, dominators, help seekers, and special-interest pleaders.

Whichever system you prefer, you want to build a team that capitalizes on people’s differences by having everyone play to their strengths and compensate for their teammates’ weaknesses. A good team improves its performance by making sure that everyone is in a role that is right for them.

One way of doing this is to use a tool such as a responsibility assignment matrix (RACI matrix). RACI stands for the four types of responsibility typically undertaken: responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed. A RACI matrix is a visual tool that indicates the responsibility each person holds for a particular activity or work item. By assigning teammates responsibilities that are a good fit (and appropriate for their skillsets), you ensure that you’re getting the best from your team.

A similar technique for task allocation is the BALM method for (Break down, Analyze, List, and Match). It’s a four-step method that involves breaking down the team’s goals into discrete tasks, analyzing the skills or competencies required to complete each task, listing the skills and competencies of each team member, and then matching team members to tasks accordingly.

Teams develop and behave differently as they pass through a number of developmental stages.

The framework most commonly used to illustrate team development is known as Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing and was created by a psychologist named Bruce Tuckman in the mid-1960s. In 1977, Tuckman added a fifth stage, Adjourning, though it isn't consistently referred to today.

Here’s a quick rundown of the Tuckman framework:

Forming:Teammates are excited but nervous about the work. They act to orient themselves with the group, introducing themselves and asking questions. Though some may be anxious about the project — particularly if they have never worked with this team before — feelings are mostly positive.

The forming stage is when the foundations for teamwork are laid. Activities include defining the team’s goals and purpose, teammate bonding, and deciding the rules and processes by which they will operate.

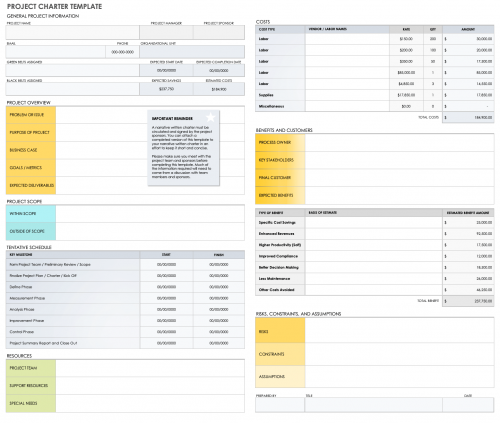

The forming stage is the foundation that teamwork is built upon, and not getting off to a good start can mean more difficulties during the storming stage. So it’s a good idea to plan and conduct a formal team orientation that facilitates introductions, goal setting, and rule defining. This is also a good time to create a team charter, which is a document that formally defines a team’s purpose, scope, goals, and deliverables. Learn more about creating a team charter.

Download a Project Charter Template

During this stage, try icebreaker games and other activities that help the team bond. Check out these great resources including team-building questions, team-building games and experts’ favorite team-building activities and exercises.

Storming: Storming usually occurs fairly quickly after a team begins its pursuit of its goals. Even the best-laid team strategies don’t always go according to plan, and the early excitement quickly ebbs. As the team’s progress slows, members of the team become frustrated, and this is the stage at which conflict is most likely to break out.

In the storming stage, teammates must negotiate with each other to manage and refocus expectations. Openness in communication is vital, and it’s not uncommon for teams to revise the way they approach tasks or problems based on the results of team negotiations.

Norming: Norming marks the gradual reduction of conflict within the team, as members come to terms both with what the team is supposed to achieve and with what other people bring to the team. Cohesiveness increases, and members of the team start feeling more comfortable with their teammates.

During the norming stage, teams typically embed some lessons learned during storming. Teammates may make more of an effort to communicate and to coordinate their efforts. The focus shifts from the team’s interpersonal relationships back onto the team’s tasks. Productivity increases.

Performing: By the time a team reaches the performing stage, it is running like a well-oiled machine. Teammates have learned to work together and are coordinating their efforts most effectively. Synergy is at its peak. As a result, individual members’ satisfaction with the team is usually high.

A team in the performing stage will make near-optimal progress towards its goals. Interpersonal relationships are good, but efforts to maintain and enhance them must continue. The team looks forward to celebrating progress milestones and eventual completion of project objectives.

Adjourning: As a project winds to a close, team members generally feel satisfaction with their performance, though it’s not unusual for some to be nervous about what comes next. It’s important to make sure that motivation doesn’t flag, and that the team finishes the project strongly. It’s also vital to check and ensure the quality of deliverables.

An adjourning team should take time to review their overall performance and to share lessons learned. This is also a great time to celebrate the team’s achievements.

One alternative to Tuckman’s framework is the Z Process. The Z Process is similar to Tuckman’s framework in that it has four stages, but it doesn’t focus on team dynamics. Instead, it describes four stages during which a team comes up with an idea and brings it to life. The Z Process suggests that there are individuals whose natural strengths correspond to each of the four stages. If you know what your team members are good at, you can have the right people take charge of the project at each stage.

The first Z process stage is creating: when people come up with ideas for what the project’s goals are and how best to achieve these goals. This is where creative thinkers, or creators, shine. No idea is off the table.

The second stage, advancing, involves gauging and building interest in an idea. Advancers excel at getting people to buy into an idea before the team starts to refine it.

Refining, the third stage, is all about critiquing and amending an idea so that it’s practical and implementable. Project details are fleshed out in this stage, and a plan of action is created to execute the project. Refiners, strong critical thinkers and detail-oriented planners, take charge here.

Executing is the final stage, when the plan is put into action. Executors are good at implementing plans and bringing ideas to life.

Team assessments provide more value to the team at some times over others. Unfortunately, team assessments are too often done only after things go wrong. While this is a perfectly legitimate reason for an assessment, organizations can reap more benefits when they do not think of team assessments only as a response to difficulty. Conducting assessments before problems arise can avoid or mitigate them as well as potentially save time and money.

Here are some good times to do a team assessment:

Team-building experts say early in the team life cycle is a prime opportunity for a team assessment. Make sure team members get off on the right foot by learning about each other’s strengths during the forming stage.

That can reduce conflict that occurs during the storming stage. These assessments are also useful for introducing new members to a team, since turnover isn’t unusual. When teammates haven’t met each other before (such as with new teams or remote teams), or when getting things right the first time is critical (such as with startups), these assessments lay a strong foundation for the team.

Reactive assessments are usually conducted during the storming stage, which is when problems are most likely to appear. Even if the forming stage sets a strong foundation in terms of interpersonal relationships, conflict can rarely be eliminated.

At this point, some team assessments help members negotiate and grow past their differences. The storming stage is also a good time to use an assessment to determine team performance baselines, so you can compare performance in the norming and performing stages. If conflict is resolved successfully, you should see performance improvements.

Team assessments also offer value to already established teams, especially when there is a change in organizational framework or when the team is preparing to tackle a new project that is different from those they have done before.

With the variety of tools available, you can focus your team assessment on different aspects of teamwork. Let’s look at some of these.

Feedback

Feedback is integral for individual growth, both as members of teams and as individual contributors. Good feedback is an honest, fair exchange of information and opinions on how people are performing. Delivered effectively, it’s an excellent source of firsthand advice that will help people advance themselves and their careers.

Delivering feedback effectively can be a challenge. Feedback should not be unnecessarily harsh nor put people down — quite the opposite. Remember you are trying to motivate the individual to adopt the desired behavior. So you want him or her to leave the encounter feeling that success is possible and with a clear idea of what they need to work on. Make sure you only give feedback in private, and if it is prompted by a specific incident, deliver it after.

Experts generally recommend starting feedback on a positive note, appreciating a person for what they have done well. This allows the person receiving feedback to relax, and they usually become more receptive to criticism.

If you are the person delivering the feedback, prepare your comments beforehand so you stay on topic and remain professional in the session. Make sure you can cite examples to illustrate your feedback. Anticipate questions, explanations, or objections the individual might have and think through your responses in advance. Good feedback is specific and actionable, and you follow up to encourage people to make improvements in the areas highlighted.

We’ll briefly discuss two models for delivering feedback to team members: the GROW model, which can be applied by a leader for a junior teammate, and 360-degree feedback, which is delivered by a person’s teammates.

GROW: This model stands for Goal, Reality, Options, and Way forward. It’s a coaching technique designed for team leaders who want to help members progress. The GROW process begins with the team member identifying a progress goal that is both SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Time-bound) and compatible with both the person’s individual interests and the team’s interests.

The next step is determining the team member’s reality —how far they are from the goal. Then the team member identifies their options for meeting the goal. The coach, or team leader, guides both of these assessments. To end the session, the coach has the team member find a way forward. He or she decides upon concrete steps to achieve the goal. The team member leaves with a plan to put this idea into action.

360-degree Feedback: A set of feedback techniques designed to gather information from people in a full circle around the individual — not just supervisors, but teammates, coworkers, and customers. It’s an excellent way to elicit feedback for team members. After all, few people know you better than your teammates, who regularly observe your behavior firsthand. 360-degree feedback is popular because it’s more holistic than single-point feedback (like from a boss). The process also reduces bias in the assessment process. However, it’s a complex system that assumes that everyone involved knows how to give fair and effective feedback. Also, the fact that feedback is delivered anonymously means it must be accepted at face value, and there’s usually little room for further discussion.

360-degree assessments use 360-degree feedback to create holistic evaluations. You’ll see them in assessments of teams or individuals with multiples interfaces, and especially for leadership assessments. The assessment design means they are able to measure performance in a large number of competencies, including hard skills such as strategic orientation, goal setting, decision making, delegation, achieving results, collaboration, and political and organizational savvy, and soft skills such as positivity, respect, communication, integrity, courage, self-awareness, and concern for others.

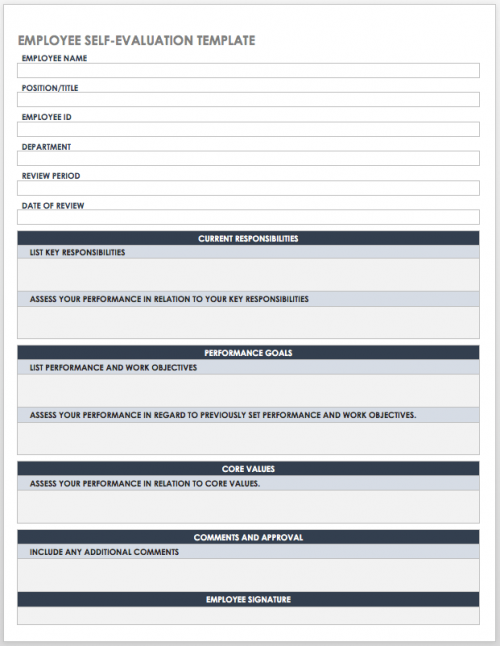

Doing self evaluations can also be enlightening. You can download this form as a starting point.

Download Employee Self-Evaluation Template

Vision encapsulates what the team is striving to achieve. It motivates and guides a team to achieve its goals. Since vision is such an important contributor to a team’s sense of purpose, the best teams spend time developing and understanding their vision. To ensure buy-in to a team’s purpose, make sure everyone participates in developing the team vision.

A team’s vision represents the basis for managing performance. You can think of performance management as the process by which organizations allocate, assign, and use their resources to meet the objectives outlined in their vision statement.

Teams will can also identify KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) by which to assess their own performance. Commonly tracked KPIs for teams include customer satisfaction, project cost and schedule variance, missed deadlines, and process costs. Avoiding micromanagement (which can lead to employees feeling stifled and frustrated, especially if they’re creative people) and effective delegation of duties are also indicators of good team management.

This participation in developing team vision also enables management by objectives, a management technique introduced by Peter Drucker in 1954. It aims to increase employee motivation and buy-in by giving staff a say in setting organizational objectives.

These organizational objectives translate into personal objectives for each employee, and employees are encouraged and rewarded for meeting their personal objectives. In the long run, success in meeting personal objectives is directly connected to success in meeting organizational objectives. This approach can be scaled down to translate team objectives into personal objectives.

According to Bruce Tuckman’s four-stage team development model, team conflict is inevitable. That’s because people vary in their perspectives, values, and working styles. For teammates still getting to know each other, some degree of disconnect is likely.

When these differences aren’t dealt with, things can escalate. Experienced managers and team leaders typically build some time into the schedule for teams to hit their stride, but delays beyond this can be expensive, in terms of both time and money.

So team leaders need to be experienced in the basic principles of conflict resolution: listening closely and treating team members fairly and equitably; focusing on shared interests and attacking the problem, not the people; and encouraging clear, honest communication to find a way forward. Role play, a tool for helping people step into each other’s shoes, can help.

As we noted earlier, effective teams are distinguished by their synergy, and good teamwork is based on team members playing to their strengths and compensating for each other’s weaknesses. But team member development also requires improving in areas of weakness.

Let’s look at Edward de Bono’s six thinking hats as an example. Being especially proficient in one thinking style certainly doesn’t mean there’s no need to improve the others — even if other teammates already excel at those skills. Team members are inherently dissimilar; they bring different combinations of knowledge and experience. So improving thinking and communication skills allows people to leverage their knowledge and experience for the team’s benefit.

One important tool in team member development is the training needs analysis, a method to determine who needs to be trained, what they need to be trained in, and how best to train them. A training needs analysis reconciles a team’s need for specific competencies with the team member’s interest in being trained, and ensures that training, when delivered, is effective for both the trainee and the team.

Download Employee Training Plan Template

It's worth discussing a couple of approaches for managing team members: Theory X and Theory Y, and the Blake-Mouton managerial grid. They both address different ways of seeing, interacting with, and managing the world.

Developed by social psychologist Douglas McGregor in the 1960s, Theory X and Theory Y are shorthand for two contrasting ways of viewing a workforce. Theory X can broadly be described as a pessimistic opinion of the average worker: He or she doesn’t enjoy work for work’s sake, has little ambition of his own accord, and works only in expectation of rewards. Theory X also views subordinates as inferior to managers in terms of both intellect and willingness to exert effort, which means they need constant oversight to work properly. Theory Y, on the other hand, is optimistic, viewing people as intrinsically motivated actors who actually enjoy the work for its own sake, and for whom remuneration isn’t the sole reward. It views subordinates as intelligent and responsible in their own right, needing minimal supervision.

While Theory-X-style managers enjoy a consistently higher quality of output, Theory-Y-style managers tend to have better relationships with members of their teams. Research suggests that the nature of work to be performed is the best determinant of which management style is more suitable. As a general rule, managers obtain better results by using Theory X to manage workers who perform repeatable tasks, such as workers in the manufacturing industry. Conversely, workers who undertake non-repeatable, creative, or intellectual tasks respond better to Theory Y.

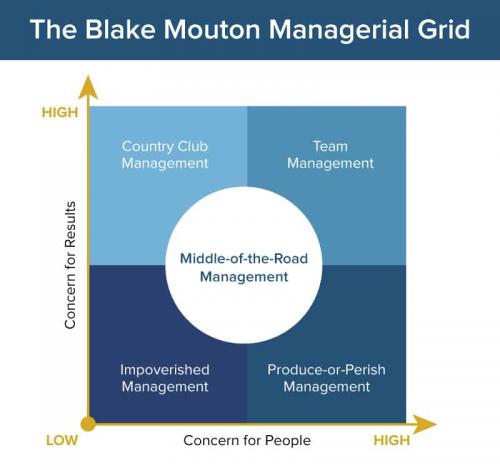

The Blake-Mouton managerial grid is a visual representation of how managerial styles differ in how people focused and task/results focused they are. Being people focused means you prioritize your team members’ happiness. Being task or results focused means you prioritize task requirements and deadlines.

The Blake-Mouton grid doesn’t encourage striking a balance between the two: it terms this “middle-of-the-road management.” Instead, it encourages managers to develop both management styles to their fullest possible extents, thus maximizing both team members' happiness and team performance.

The Blake-Mouton model plots these two orientations on different axes. Managers or leaders fall into different quadrants based on how they weigh people and results. This indicates their leadership style.

Synergy relies on two things: individual strengths (which we’ve discussed) and effective collaboration. Teams need people who complement each other, but they must coordinate their work.

Some aspects of effective collaboration, such as communication, tend to deepen naturally with time. Others, such as group cohesion, have to be actively worked on. The members of a successful team are all oriented toward achieving the same purpose, and they have the same idea for how to get there. When team members’ orientations diverge, the team’s ability to collaborate — and their productivity — takes a hit. If goals diverge further, tensions or even conflict may appear, costing the team more time and money.

To preserve the team’s orientation, consensus must be developed and then maintained. This can be tricky since you do not want to go too far in the opposite direction and impose a “consensus” from the top down.

A second risk (though one that’s not usually considered) is groupthink, the tendency of groups to sacrifice creativity to conformity. Teams who fall victim to groupthink have little trouble developing consensuses, but this is only because they actively refuse to consider anything beyond a small subset of ideas and do not want to engage critically with unfamiliar or dissenting alternatives.

There are, however, team learning and negotiation techniques that can reduce the effects of groupthink. One of these is concept attainment, a teaching technique that can be used with groups of middle-school age and older. Concept attainment promotes understanding of concepts via observation, rather than using concrete definitions.

For example, a concept-attainment-style lesson on different schools of art might show students several different art works and encourage them to form definitions for each school based on common characteristics. The same can be done with groups of adult learners. The technique relies on the group building a consensus to define concepts, but it also reduces groupthink by removing the boundaries created when concepts are defined outright. This tends to make alternative definitions seem somehow wrong.

Another technique for building consensus while minimizing groupthink is the Delphi method. This technique was developed during the Cold War to project how technology might change warfare. But it can be used to develop consensus around any continuous variable.

To begin the exercise, each member anonymously estimates a given variable. The group then reviews the anonymous estimates, and sets a baseline for the next round of estimates; the process is repeated until a consensus is reached. The fact that estimates are made anonymously and concurrently prevents groupthink, as each participant is not aware of the limits that other participants impose on their own estimates.

Earlier, we discussed how team assessments are based on theories of what makes teams work. One of the most widely used theories comes from business consultant Patrick Lencioni’s 2002 book, The Five Dysfunctions of a Team.

As the title suggests, the national bestselling book traced problems with teamwork to five root causes, which Lencioni termed “dysfunctions.” Today, a consulting company called The Table Group, which Lencioni and his colleagues founded in 1997, offers online team assessments based on Lencioni’s Five Dysfunctions model. A number of other consulting companies, such as Performance Management Partners, also offer team assessments that draw from Lencioni’s model.

As you’ll see, starting with the absence of trust, each dysfunction gives rise to those that come after it. This is why the Five Dysfunctions are represented as levels on a pyramid, with the absence of trust represented as the foundation of the pyramid.

Five Dysfunctions of a Team

As Defined by Patrick Lencioni

Many team assessments are modeled on Patrick Lencioni’s Five Dysfunctions. If one of these suggests that your team needs to work on certain dysfunctional behaviors, here’s how to go about it:

Build Trust

A lack of trust, says Lencioni, is the root of all dysfunctional behavior. But since trust is an inherently personal relationship, how does one improve it throughout a team? The answer: You can’t really foster trust, but you can put people in situations that encourage them to open up to each other, because openness can breed trust. This works especially well when a team is still young, but it can work with people who already know each other, too.

Try having team members complete a personality instrument such as the MBTI or Everything DiSC Workplace, and then share their results with the team, with insight into how they think their personality type and natural traits influence their behavior. Otherwise, try using an icebreaker exercise to get people to open up and talk about things they wouldn’t normally discuss at work.

Open-ended questions that encourage people to talk about themselves are the best choice here. (For more on team-building questions, check out our comprehensive resource that includes example questions to try with your team.) And lastly, make sure your team members see each other face to face often. This isn’t a problem for many teams, but it can be for cross-functional teams who don’t work in proximity and remote teams, and it’s generally difficult for people to trust each other when they don’t interact face to face very often.

In teamwork, conflict isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Remember, it’s necessary to develop ideas and to ensure buy-in to the team’s purpose. Problems arise when team members are not willing to engage in conflict at all, even if it’s productive. This can happen for a couple of reasons.

Sometimes, team members may not be confident enough to challenge senior figures within the team, or they may keep clear of conflict out of desire to be accepted by everyone in the team., This is a reluctance to engage in conflict at the individual level. At other times, however, the reluctance to engage in conflict is more a structural feature of the team, such as the presence of naturally dominant personalities within a team, or intra-team politics that means those in conflict aren’t treated equally.

At other times, the avoidance of conflict at a team level may be a function of a general reluctance to deal with conflict among a majority of team members.

To address individuals’ reluctance to engage in productive conflict, a personality or styles assessment such as the MBTI or the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Instrument can help people understand their natural response to conflict, and how they might become more willing to participate in productive conflict. If results are shared with the team, these tools have the added benefit of enhancing mutual understanding of conflict styles, which can make things a little easier for everybody.

To address a lack of productive conflict at the team level, set clear expectations for how team members are supposed to interact with one another: fairly, equitably, critically, and with an open ear. You may also want to set rules for engagement; some teams, for example, allot people uninterrupted time to speak during discussion sessions.

These things can help productive conflict emerge during meetings, which can otherwise be intimidating for those reluctant to engage in conflict. If your team displays a general reluctance to deal with conflict, talk to the team leader about having someone to ask the tough questions and thrash out the decisions that team members are reluctant to make.

If team members don’t trust each other, they’re unlikely to engage in productive conflict, and if team members don’t engage in productive conflict, they’re unlikely to see team decisions as representing shared perspectives. This results in a lack of commitment to team decisions and team goals, which can cripple a team. This kind of commitment problem is best treated by addressing the underlying causes: lack of trust and reluctance to engage in conflict.

Lack of commitment can spring from other causes besides a lack of trust and productive conflict. Sometimes teams struggle to set goals for themselves, or the goals they set are unclear. In this case, it’s the team leader’s responsibility to steer the team towards closure and clarity.

When decisions are made in a meeting, review them at the end of the meeting, and make sure the communication is cascaded. Lencioni explains the cascading communication tool as a way of having leaders communicate key messages to their staff, who do the same with their staffs and so on. Try setting a thematic goal, which, according to Lencioni, is the “single, temporary, and qualitative rallying cry shared by all members of the team.”

Sometimes, a team makes decisions based on the views of a small majority. When this happens, you need to ensure that the whole team commits themselves to the decision — but how?

In cases like this, it’s important to recognize that people will not commit themselves to a decision if they don’t believe it’s the right decision. (That is, if they fear it’s unwise and that things will go wrong.) But since a compromise does need to be reached, have the team set up a contingency plan that allows them to revisit the decision. This removes people’s fears of assuming that one bad decision will spell the end of the project, and allows them to dedicate themselves fully and without worry to a decision they may not have fully favored.

Articulating the worst-case scenario might also be a viable tactic here. Sometimes, it helps for people to know that a bad decision probably won’t lead to a catastrophic outcome. Also, some members of your team might respond to hearing what might go wrong by committing themselves at least to ensuring that this doesn’t happen.

Like a lack of commitment, the absence of accountability is a result of preceding dysfunctions. In the same way, it’s also best addressed by building trust, increasing acceptance of productive conflict, and increasing team commitment.

That said, there are some things a team leader or supervisor can do to ensure the team practices accountability. Start by having the team identify behaviors that are potentially harmful via a team effectiveness exercise, where team members communicate each other’s positive and negative behaviors. Then, publish a set of behavioral standards which the team is expected to follow. It’s much more likely that team members will follow — and make sure that others follow — a code of conduct that is clearly enunciated.

You can also build accountability into the team’s operating structure. Get each team meeting started with a lightning round, where team members quickly report on their progress since the last meeting. And make it a point to conduct regular reviews of progress towards the team’s thematic goal.

In theory, you can go a long way towards increasing a team’s focus on their results by addressing the dysfunctions that precede a lack of attention to results. But you can also cultivate this directly.

First, have team members publicly commit themselves to the team’s thematic goal as that by itself with increase follow-through. Also, make sure that a team's thematic goal is in clear alignment with organizational goals. If team members understand how their work contributes towards the organization as a whole, and if they buy into the organization’s purpose, they will see the relevance of their efforts to the larger effort. You can also incentivize team performance by having compensation programs reward team-based achievements.

Lastly, remember that in most organizations, people shoulder a number of responsibilities besides their membership in a team. A general rule of thumb is to have people prioritize their responsibilities to the teams they lead over the teams they participate on.

Lencioni’s five dysfunctions offers a roadmap for what not to do. If lack of trust leads to fear of conflict and a variety of other problems, it follows that building trust would reduce fear of conflict and prevent the succeeding dysfunctions: lack of commitment, accountability, and poor results.

This is the idea behind The Five Behaviors of a Cohesive Team, a collaboration between Lencioni and Wiley Workplace Learning Solutions. The Five Behaviors is a team development program that reverses Lencioni’s five dysfunctions to propose a model for functional teams. If the five dysfunctions are the root causes of problems with teams, the five behaviors help you avoid those problems.

The five behaviors are simply the reverse of the dysfunctions: trust, (productive) conflict, commitment, accountability, and results. Just like the dysfunctions, each positive behavior breeds the next. By building trust, you lay the foundation for an effective team.

There are several things to keep in mind when selecting an assessment for your team and your situation. No single assessment works for all situations or teams. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses.

Cost, as always, is a consideration. Some well-regarded online assessment tools can be used for less than $20 a person. But the most effective and sophisticated tools cost more and are usually part of a package that involves a consultant to oversee the assessment, explain the results and draft action plans. These engagements typically run into thousands of dollars.

Before selecting the assessment tool, isolate what you want to learn about your team. Are you hoping to understand team members’ personalities better? Are you looking to gauge the quality of team processes, such as communication or delegation? Or are you trying to assess your team leader’s leadership skills?

If you have a team that’s already facing problems, you’ll need to identify the broad area within which the main problem lies, and then pick an assessment that specifically targets that area. Always aim to address the biggest problems first.

In fact, shoot your team an email, or have them answer a few questions with a simple online survey to get their input on the type of assessment needed. Here’s an example of one.

During the assessment, you’ll need to plan time accordingly. If the assessment is to be followed by a discussion, workshop, or group facilitation, run the assessment before you start working with the group, so you have the results to shape the rest of your program. Make sure all team members participate. If you're facilitating the session, make sure you set a good example. Keep in mind that even within each broad assessment category, different assessments are designed for different purposes. It’s important to understand exactly what an assessment is measuring and how, so you can determine if the assessment is right for you.

For example, if you’re focusing on team communication, don’t talk over people. Better still, bring in a professional to run the assessment. They’re typically more experienced and are not tainted by organizational politics, so they generally get more accurate results.

Lastly, remember that team assessments are simply an evaluation tool that cannot necessarily override the nuance and subjectivity involved in teamwork. If something works well for your team, don’t feel you have to abandon it just because an assessment says you should. Trust your team.

Personality and behavioral style assessments try to help individuals understand their behavior as a function of naturally emerging personality or style traits. Understanding your own behavior helps put your strengths into perspective, while allowing you to understand how your coworkers perceive you. Your coworkers do the same, which creates a greater, team-wide understanding of why people behave the way they do.

Personality and behavioral style assessments are designed to be taken by everyone in a team or workplace as a way of understanding how coworkers can work together most effectively and minimize frustration.

These tools are not suited to solving specific problems, but they provide a common language for people to understand workplace behaviors. By understanding work “styles," as these assessments term them, you’re better able to appreciate other people’s perspectives and communicate and work together more effectively.

Tips: Assessments of this type often produce lengthy personality reports - allow your team some time to digest them before debriefing. When working with teams, raise the question of behavior style representation in your team. Does your team have a single dominant style? What does that mean for their work?

Personality and behavioral style assessments can be tailored to highly specific skill assessments. One example is the SPQ*GOLD Sales Preference Questionnaire, which measures sales call reluctance —the degree to which individuals are comfortable initiating first contact with potential customers — in prospective salespeople.

Examples: Everything DiSC Workplace, Hogan Personality Inventory, Gallup StrengthsFinder, Social Style, Riso-Hudson Enneagram Type Indicator, FIRO-B, Birkman Method Personality Assessment

Leadership assessments usually have two main aims: helping leaders understand the behaviors they exhibit (their leadership style), and helping leaders understand how they are seen by the people around them. These assessments usually look at such things as communication, creativity, decision making, planning, goal setting, progress monitoring, team communication, coaching, and operational knowledge. Some are 360-degree assessments, gathering data from people at all levels of the organization who interact with the leader to create a holistic picture.

Leadership assessments are designed to be used with people who have occupied leadership positions for long enough to have settled into a reasonably consistent leadership style. They can be used to troubleshoot specific problems or to broadly develop a leader’s toolkit.

Tips: It’s important to do a leadership assessment in a way that does not undermine the leader with his or her team. Gather feedback discreetly and as always, discuss the results privately.

Examples: LPI 360, Lominger/Korn Ferry Voices 360, Checkpoint 360, Everything DiSC Work of Leaders

Team assessments are based on diverse approaches. Some view teams primarily as sets of individuals fulfilling different roles, and explain team success as a function of a team’s ability to balance these roles (think Z Process strengths or the Belbin roles). Some focus primarily on the nature of a team’s processes (their communication, levels of trust, practice of holding team members accountable, etc.), and some examine the quality of a team’s outputs, treating these as proxies for overall team health.

Think about your reason for conducting the assessment. Are you trying to help new team members understand each other better? If so, pick an assessment that focuses on individuals’ roles as part of a team. Is your team running into communication problems? Choose a tool that focuses on the subtleties underlying this problem. Are your team’s results suffering? Select an assessment that examines performance factors.

Tips: Behavior style assessments and leadership assessments can also be viewed and used as team-building assessments. The former increases interpersonal understanding, which improves collaboration. The latter improves leadership, which can strengthen team efforts.

Examples: Shadowmatch, Everything DiSC Team Dimensions, The Five Behaviors of a Cohesive Team, The Table Group team assessment, Linkage Team Effectiveness Assessment, Harrison Assessments Employee Engagement

While assessments that focus on leadership and behavior styles are helpful for all teams, new teams should prioritize trust, which according to Patrick Lencioni, is the foundation of all good teamwork.

Assessments may focus either on the trustworthiness of individual team members or shared trust within a team. Since trust is a highly abstract concept, different assessments measure it in unique ways. Regardless of which trust assessment you choose, however, some determinants of trust appear to be almost universal — comfort with intimacy, reliability, integrity, and loyalty. And the end goal of all trust assessments is the same: helping team members build better relationships.

Trust-building exercises work well with new and newish teams because of Lencioni’s observation that a lack of trust is the root of all team dysfunction. While levels of trust may generally be lower among new teams, their newness also makes them more receptive to trust development exercises, which can double as team bonding exercises. If a lack of trust is a problem, address it early on, before it can spiral into other problems that hurt the team’s work.

Tips: Trust-building exercises can be difficult to conduct because many determinants of trust are really moral characteristics. Team-building games are often a great way to get around people’s natural discomfort with overt trust-building exercises.

Examples: Trust Quotient, Speed of Trust, 12 Dimensions of Trust, Everything DiSC Team Dimensions

Tools for building understanding among team members usually involve some aspect of learning about one’s self in order to understand other people. This is especially true for the Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) and the Thomas-Kilmann Instrument (TKI), but it's also the way many icebreakers work. By revealing how people think, act, and behave — usually in terms of comparing themselves to others — these exercises build mutual understanding. This fosters empathy and better communication.

The MBTI is a personality inventory that classifies people into one of 16 personality types according to how they perform on four continuums. It’s a big-picture view of how people see the world and what functions they’re best suited for. The TKI is an assessment of how people behave in conflict situations, and it’s specific to helping people understand how they approach conflict.

Although it’s tough to go wrong with tools to improve understanding in almost any situation, think about what you’re hoping the team will take away from the assessment.

Tips: Exercises to build understanding can be fun. Try using some funny icebreaker questions to kick off - they’ll relax team members and encourage them to be more forthcoming. Find out what activities team-building experts recommend.

Examples: MBTI, icebreakers, Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument

If the cost of a consultant is prohibitive, or if traditional assessments models don’t offer what your team needs, you might opt for a do-it-yourself assessment.

If you’re thinking about conducting your own assessment, ask yourself what you’d like to achieve. First, who or what is the assessment supposed to evaluate? Are you interested in the nature of a leader, an individual team member, or a team as a whole? Secondly, is there a particular problem you’re trying to address? Or are you conducting the assessment to improve general performance and reduce the probability of problems in the future?

Answering these questions will help you to determine whether you need an assessment for individuals, teams, or leaders, and whether you need an assessment that targets a specific area of concern or one that aids overall development.

Some consultancies offer to help you customize team assessments based on your organization’s particular needs. Let’s look at a couple of these customizable assessments — the Leadership Gap Indicator and KEYS to Creativity and Innovation, both offered by the Center for Creative Leadership.

The Leadership Gap Indicator is designed to help organizations understand where and how leadership training efforts are best directed. But organizations may define good leadership in different ways. Leadership might entail one set of competencies in one organization or industry, and a completely different set in another. To facilitate this, the Leadership Gap Indicator is based on a model of effective leadership that can be customized to feature different leadership competencies, depending on the participating organization’s specific needs.

KEYS to Creativity and Innovation (KEYS) is an assessment of how conducive a team or organizational climate is to creativity and innovation. It works by surveying employees to gauge their perceptions of the climate.

However, some organizations are not necessarily supposed to be conducive to creativity and innovation. For example, you wouldn’t expect as high a degree of receptivity to creativity and innovation in an assembly line as a marketing or public relations department. In recognizing this, KEYS allows organizations to choose the normative group — that is, the industry type to which their organization’s climate is compared.

Another low-cost, self-led option is Gallup StrengthsFinder test. The company says it has been taken by more than 16 million people and identifies individual's’ natural strengths. It's “StrengthsFinder 2.0” book and other resources can help you understand and apply the results.

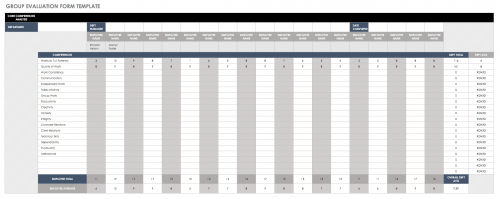

If you want to see how far you can get with DIY assessments, start simple. Have a few managers assess team members privately and then compare results. Here’s a form you can use.

Choose the Right Team Assessment Tool

Problem/Situation

Tool Type and Examples

Notes

Best for cross-functional teams

Personality assessments (e.g. MBTI), strengths assessments (e.g. Strengthsfinder), specialized performance assessments, DIY performance assessments

When working with individuals in cross-functional teams, use easy-to-understand assessments that provide a common language to help teammates understand each other. For evaluating team processes and performance, industry or area-specific assessments are a better choice than general performance assessments, which may not be relevant to your team’s specific function. Can’t find a performance assessment that’s suitable for your team? Pick one that comes close and adapt it.

Best for new teams

Simple personality and strengths assessments (e.g. MBTI, StrengthsFinder, Social Style), tools for building trust (e.g. Trust Quotient, Speed of Trust), tools for building understanding (e.g. icebreakers)

For new teams, stick with simple, easy-to-understand assessments like the MBTI, which some team members will already be familiar with. Don’t use performance assessments for new teams, as they’re not very useful markers of team ability until basic trust and understanding have been developed. Instead, pick tools that focus on building these vital foundations.

Best for mature teams

General performance assessments (e.g. Team Effectiveness Assessment by Linkage), specialized performance assessments, DIY performance assessments

Teams that have been working together for a while should have fairly robust levels of trust and understanding, and members will already know each other quite well, too. Assessments that focus on measuring aspects of effectiveness and productivity are a good choice. You may want to pick an assessment designed for use with specific team types.

Best for trust problems

Tools for building trust (e.g. Trust Quotient, Speed of Trust)

Patrick Lencioni’s “Five Dysfunctions of a Team” says an absence of trust is the root of all team dysfunction. If you think your team has a trust problem, use a team trust assessment and trust-building exercises to identify and rectify it as soon as you can. Until your team resolves their trust problems, they won’t be able to operate to their full potential.

Best when problem is lack of shared vision

Tools for building understanding (e.g. MBTI), tools for building trust (e.g. Everything DiSC Team Dimensions), leadership assessments (e.g. Everything DiSC Work of Leaders)

It’s tough to pinpoint the causes of a lack of shared vision. Are your team members not speaking the same language? Is there a lack of trust? Or is the team leader not helping the team to develop a vision? Since a lack of shared vision is usually very apparent to everyone in a team, it’s worth talking to the team first to find out what they think is the problem. The team’s insights on what isn’t working should help you figure out what needs to be fixed.

Best when there is conflict

Tools for building trust (e.g. Trust Quotient), tools for building understanding of conflict (e.g. Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Instrument)

Conflict in a team isn’t necessarily a bad thing, because it ensures buy-in to the team’s purpose, and thus the commitment of all team members. Besides, some amount of conflict is natural. If, however, your team suffers from harmful conflict, you can target it in two ways: with Patrick Lencioni’s Five Dysfunctions model to target an underlying lack of trust (which may be the reason behind harmful conflict), or to tackle the conflict itself by helping team members understand how they approach conflict.

Best for project teams

Targeted tools that focus on behaviors and interpersonal preferences (FIRO-B)

Project teams may be thrown together on short notice, and because they are focused on executing their project, they don’t have time to bond. Practical, outcome-oriented assessments work best here.

Best for start-ups

General performance assessments (e.g. The Table Group team assessment)

Teams working at startups tend to be homogenous and motivated, and it’s quite likely that they’ll comprise people who have already worked together. As such, help them get off the ground quickly, and to achieve consistent improvement. Pick a general performance assessment that provides a broad overview of the team, so they can focus on any problem areas and aim for quick, measurable improvements.

Best for remote teams

Personality assessments (e.g. MBTI, Hogan Personality Inventory), tools for building understanding (e.g. icebreakers), individual performance metrics, and tools that enhance communication

Managing a remote team is considerably more difficult: It’s tough to make sure people stay on track, it’s difficult to motivate employees via digital channels, and the lack of social interaction means commitment to colleagues can be lower. To combat this, try using personality assessments to see if people are actually suited to remote work. Give your remote workers reasons to engage and bond with each other, even on a small scale. Plus, set and measure short-term performance metrics so you can keep an eye on productivity.